The Empirical Case for Two Systems of Reasoning

Sloman*, Steven A.

Psychological Bulletin 119, no. 1 (1996): 3

https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.3

* Professor at Brown University

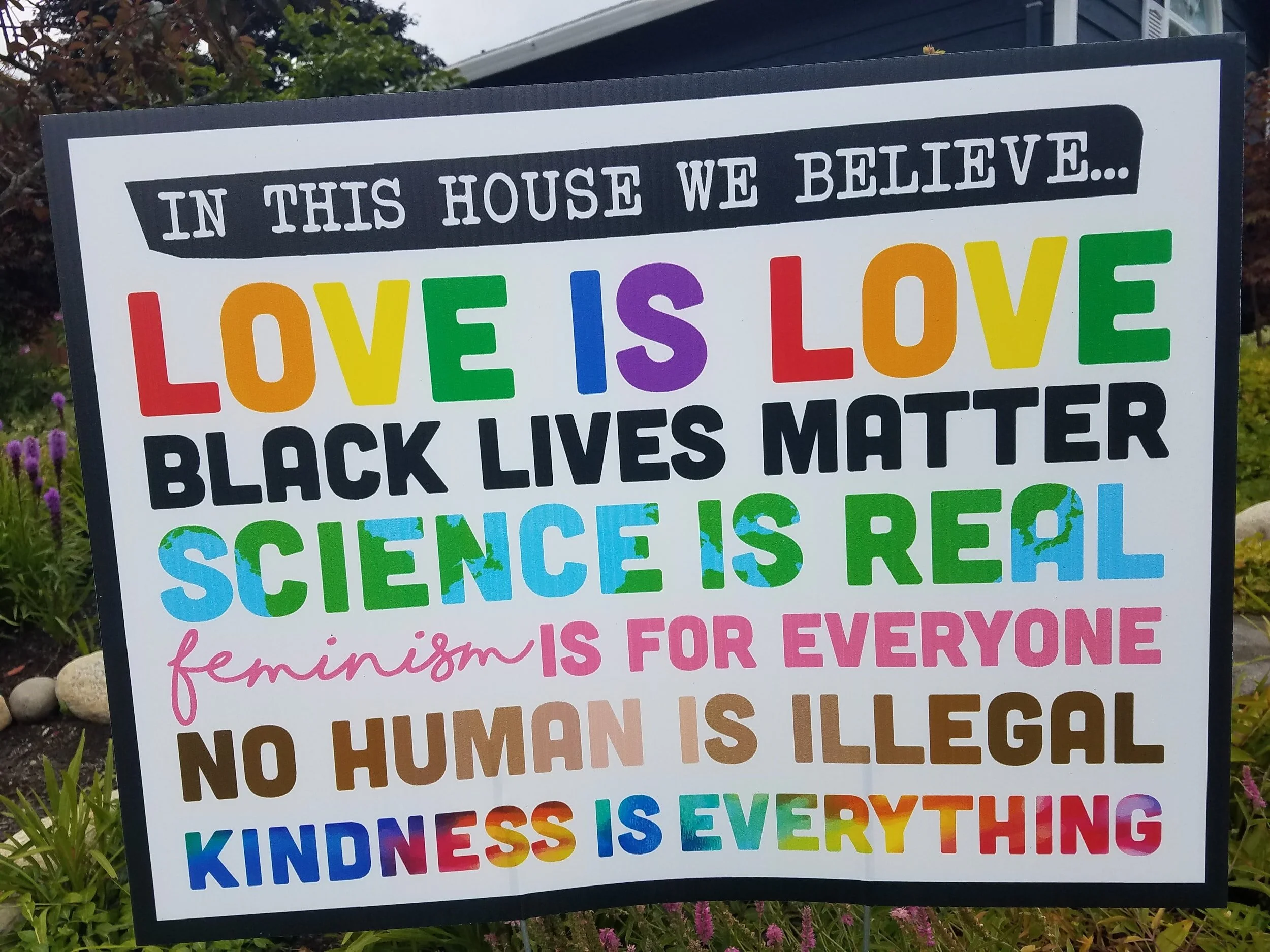

“One of the oldest conundrums in psychology is whether people are best conceived as parallel processors of information who operate along diffuse associative links or as analysts who operate by deliberate and sequential manipulation of internal representations. Are inferences drawn through a network of learned associative pathways or through application of a kind of “psychologic” that manipulates symbolic tokens in a rule-governed way? The debate has raged (again) in cognitive psychology for almost a decade now. It has pitted those who prefer models of mental phenomena to be built out of networks of associative devices that pass activation around in parallel and distributed form (the way brains probably function) against those who prefer models built out of formal languages in which symbols are composed into sentences that are processed sequentially (the way computers function).

An obvious solution to the conundrum is to conceive of the mind both ways—to argue that the mind has dual aspects, one of which conforms to the associationistic view and one of which conforms to the analytic, sequential view. Such a dichotomy has its appeal: Associative thought feels like it arises from a different cognitive mechanism than does deliberate, analytical reasoning. Sometimes conclusions simply appear at some level of awareness, as if the mind goes off, does some work, and then comes back with a result, and sometimes coming to a conclusion requires doing the work oneself, making an effort to construct a chain of reasoning. Given an arithmetic problem, such as figuring out change at the cash register, sometimes the answer springs to mind associatively, and sometimes a person has to do mental arithmetic by analyzing the amounts involved and operating on the resultant components as taught to do in school. […]

However, the distinction is not a panacea; it is problematic for a couple of reasons. First, characterizing the two systems involved in a precise, empirically consequential way raises a host of problems. Distinctions that have been offered are not, in general, consistent with each other. Second, characterizing the systems themselves is not enough; their mode of interaction must also be described. A psychologically plausible device that can integrate computations from associative networks and symbol-manipulating rules has proven elusive.

In this article, I review arguments and data relevant to the distinction and, in light of this evidence, provide an updated characterization of the properties of these two systems and their interaction. […] To preview, several experiments can be interpreted as demonstrations that people can simultaneously believe two contradictory answers to the same reasoning problem—answers that have their source in the two different reasoning systems. ”

Seligman, Martin

Psychological Review 77, no. 5 (1970): 406.